Italian "invasion" of France in June 1940

On June 10, 1940, at 16 pm, Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano received the French ambassador at the Palazzo Chigi and informed him of the following: the state of war. At 30:11 Ciano invited the English ambassador to the Palazzo Chigi and informed him in the same form that Italy considered itself a state at war with Great Britain.

Negotiations on German-Italian military operations against France were initiated on February 23, 1939 by the Italian ambassador in Berlin, Bernardo Attalico, who, under the leadership of Mussolini and Ciano, discussed this topic with German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop. At the military level, negotiations began on March 22, 1939, when the Chief of the General Staff of the Italian Armed Forces, General Alberto Pariani, met for the first time with the envoy of the Commander-in-Chief of the German Armed Forces, General Wilhelm Keitel, Colonel Enno von Rintelen, the military attaché of the German Embassy in Rome. Both sides, as reported by Germany, agreed that they would not be ready for war, like their Western adversaries (Great Britain, France and the United States) until 1942. At the same time, both sides were aware that the war could start earlier, which is why they decided to be ready for it. On April 5-6, 1939, during a meeting between General Pariani and General Keitel in Innsbruck, Pariani made it clear that the Italian army, waging war on the European continent and in the colonies, would need additional large material and material support.

B In May 1940, the German army invaded deep into France, scoring a series of lightning victories, while the General Staff of the Italian armed forces continued to struggle with the proper preparation of the army for combat. The Chief of the General Staff, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, told Mussolini that the Italian army was formally on alert, but it would take at least 25 days to go on the offensive. This situation is confirmed by Ciano, who wrote in his Diary that on June 19, 1940, Mussolini decided to attack the French immediately in the Alps, but Marshal Badoglio tried to vigorously counteract him. Ciano himself noted in a conversation with the dictator that it would not be very commendable and morally dangerous to rush into an already defeated army. The ceasefire is very close, and if our troops had not been able to break through their defenses the first time, we could have ended the campaign with a resounding failure. In addition, Germany's ally was not enthusiastic about further oppression of France. German leader and chancellor Adolf Hitler said that France in the new European order, under a friendly government, should play an important role as an ally of the Axis powers. Therefore, Hitler was not interested in dividing France between Germany and Italy.

On both sides of the front

The Italian offensive was finally launched on June 20, 1940, but it did not actually take place until June 21. A total of 22 divisions, which were part of three armies, including two armies of the first wave (1st Army under the command of General Pietro Pintor, Chief of Staff of General Fernando Gelich and 4th Army under the command of General Alfredo) were sent to attack the French positions Guzzoni, Chief of Staff General Mario Soldarelli) and one army in the strategic reserve. Both armies of the first line were part of Army Group West under the command of General Duke Umberto di Savoia (Chief of Staff General Emilio Battisti). They were to attack the French positions along the entire length of the border. The Italians were waiting for high mountains, only a few passages through them and a narrow low-lying strip on the coast. Mussolini hoped to capture Nice, the city of Savoy and the eastern part of the Rhone valley, about 100 km from French territory.

Alpine gunners prepare mules to carry mountain guns and other equipment.

Officer of the General Staff, Lieutenant (soon promoted to Captain) Luigi Marchesi, seconded to the II Staff. The corps of the 1st Army wrote that the expectations for the Italian units were huge. Meanwhile, the Italian officers were very surprised by the decision of the command and Mussolini, especially since there were many recruits and reservists in the units without proper training. No one even felt the atmosphere of war, especially the soldiers. Marquessi noted that the weaponry and equipment were inadequate and outdated.

Modern weapons were supplied to the unit for a long time, but in small quantities. As Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, Chief of the General Staff of the Ground Forces, summarized, this simply was not an agreement. Three days before the declaration of war on France and Great Britain, on June 7, 1940, Graziani wrote to the command of the Italian army in Piedmont that in the event of hostilities on the front with France, the absolute defensive nature of these operations, both on land and at sea, should be maintained. .and in the air. Only on June 14 did all the existing agreements, worked out over many months, begin to change. Six days before the onset; too late.

Even good combat training and excellent knowledge of the Alpini mountains could not change the fate of the unprepared and poorly conducted Italian campaign against France.

The 1st Army included: II. Corps of General Francisco Bettini, which included the 36th Infantry Division "Forli" (General Giulio Perugi), the 33rd Infantry Division "Acqui" (General Francesco Sartoris), the 4th Infantry Division "Livorno" (General Benvenuto Joda) and the 4th mountaineering division "Cuneense" (General Alberto Ferrero), the mountaineering battalions "Valle Stura" and "Val Maira", tank company CV.3 / 35; III Corps of General Mario Arizio, which included: 3rd Infantry Division "Ravenna" (General Edoardo Nebbia), 6th Infantry Division "Cuneo" (General Carlo Melotti), 1st Alpine Group (3 alpini battalions, 2 mountain artillery battalion, the 3rd and 4th "blackshirt" battalions; the XV Corps of General Gastone Gambara, which included the 5th Infantry Division "Cosseria" (General Alberto Vassari), the 37th Mountain Division "Modena" (General Alexandro Gloria)), 44th Cremona Infantry Division (General Umberto Mondino), Alpine Group (4 Alpini battalions, 2 mountain artillery battalions and a Blackshirt battalion) together with the 33rd and 34th Blackshirt battalions and reserve corps consisting of: the elite 7th Infantry Division "Lupi di Tuscany" - "Tuscan Wolves" (Mussolini himself, commander General Ottavio Priore was the honorary patron and member of the division), the 16th Infantry Division "Pistoia" (General Mario Priore) , 5th Division "Alpini" Pusteria" (General Amedeo de Chia), 22nd Infantry Division "Cacciatori della Alpi" - "Alpine Thoughts Vi" (gen. Dante Lorenzelli), the 1st Bersaglieri Regiment, the 133rd Panzer Regiment of the 133rd Panzer Division "Littorio" and the 1st Cavalry Regiment "Cavalleggeri di Monferrato".

The 4th Army of General Guzzoni consisted of the 1st Corps of General Carlo Vecchiarelli, which included: the 24th Infantry Division "Superga" (General Curion Barbasetti di Prun), the 59th Infantry Division "Pinerolo" (General Giuseppe de Stefanis ), 3rd Infantry Division "Pinerolo" (General Giuseppe de Stefanis). Cagliari Infantry Division (General Antonio Scuro), Alpini's Susa and Val Cenischia Battalions, Alpini's 3rd Group (11th Battalion) and the 2nd Blackshirt Battalion; IV Corps of General Camillo Mercalli consisting of: 26th Infantry Division "Sforzesca" (General Alfonso Olearo), 1st Infantry Division "Assietta" (General Emanuele Ghirlando), Alpine Corps of General Luigi Negri, to which they were subordinate: 3rd Division Alpini "Taurinense" (General Paolo Micheletti), "Levanna" Alipni Group (1 Alpini Battalion, 3rd Mountain Artillery Division), 13th Alpini Regiment, Alpini Battalions "Duca d'Aosta", "Monte Blanco", "Arditi" (assault) and the 11th battalion of "black shirts"; The reserve corps included: 58th Infantry Division "Brennero" (General Arnaldo Forgiero), 2nd Infantry Division "Legnano" (General Edoardo Scala), 4th Division Alpini "Tridentina" (General Hugo Santovito), 1- th Bersaglier Regiment, XNUMXth Panzer Regiment, Cavalry Regiment “Nice Cavalry”.

The armored units that were to take part in the upcoming operation had considerable combat experience, but already from the time of the Spanish Civil War. In addition, they had outdated and inadequate equipment - mainly tankettes CV.3 / 35, armed with machine guns, and light tanks L6 / 40 with a 20-mm automatic gun and Fiat 3000 with a 37-mm short-barreled gun. Only two divisions, Littorio and Trieste, were fully motorized. The most mobile in the individual divisions and support units were the Bersaliers, who traveled exclusively on motorcycles or bicycles.

In the Italian army, there was a significant difference between mountain and alpine (alpine) divisions. Mountain rifle divisions—specially equipped infantry divisions for operations in mountainous conditions—had an additional contingent of transport animals and a larger strength than a regular infantry division. The Alpine divisions, on the other hand, were specialized mountain divisions, all of whose personnel came from the Alpine regions, were distinguished by high physical fitness and a high level of training, and the artillerymen were masters of transporting weapons using pack animals and using them. The regiments had their own permanent artillery, sappers and auxiliary units.

Among these forces were also 28 "black shirt" battalions which were assigned to reinforce each division or operated individually in battle groups with other troops.

The strategic reserve was the 7th Army under the command of General Emanuel Filiberto Duca di Pistoia. It consisted of: the 7th Infantry Division "Lupi di Tuscany", the 10th Infantry Division "Piave", the 41st Infantry Division "Firenze", the 48th Infantry Division "Taro" and the 65th Infantry Division "Granatieri di Savoia", 102nd motorized division "Trento". and 1st coffee division-

lerii "Eugenio di Savoia".

32 Italian divisions had to resist 6 French mountain divisions and support units of the Alpine army under the command of General Rune Olri (let's not forget, however, that the combat readiness of the Italian units did not exceed 50 percent).

The 185 French army and the 315 Italian army faced each other in the first wave. In total, the Italian command sent 500 3000 people to attack France. soldiers, supported by 150 artillery pieces, and the French first line forces numbered 1929 people. soldiers. However, the French could use for defense the extensive system of fortifications created and improved since XNUMX, which was the strongest in the area from the peak of Mont Blanc to the Mediterranean Sea.

Air support for both Italian armies was to be provided by the 1st Air Fleet, which consisted of four fighter regiments, two of which - the 3rd and 53rd - were equipped with Fiat CR.42 Falco biplanes. Two divisions of the 3rd regiment operated from the airfields of Novi Ligule e Albenga (18th) and Cervere (23rd). The squadrons of the 53rd regiment were stationed at the airfields of Caselle Torinese (150th) and Casablanca (151st). The 9th squadron, also equipped with CR.42s, was also at the airfield in Gorizia. Only two squadrons (the 152nd and 153rd) of the 54th, stationed in succession at Airasca and Vergiate airfields, were equipped with Macchi MC.200 Saetta monoplanes. Each of the squadrons consisted of three squadrons. These units were intended to cover the Fiat BR.20 Cicogna twin-engine bombers. For operations against the French troops from the 3rd Air Fleet were assigned: 1st Regiment, consisting of two squadrons (17th and 157th), equipped with CR.42 and CR.32 Chirri, operating sequentially from airfields in Palermo . and Trapami, as well as the 6th independent squadron from Catania, equipped with MC.200. The following aviation units of the 3rd Air Fleet also took part in the hostilities with France: the 51st Fighter Regiment, equipped with FIAT G.50 Freccia monoplanes, with two squadrons (20th and 21st) based in Ciampino, and a squadron (22nd) with the 52nd Capodichino Regiment (G.50 and CR.32) tasked with attacking Corsica, patrolling French territorial waters and covering the bombardment of Tunisia. The 6th Regiment was soon divided and its aircraft (CR.32) were transferred to the airports of Monserrato and Alghero in Sardinia.

"The Strange War", June 10–20, 1940

On May 31, 1940, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, in a conversation with an officer of the French military mission in Great Britain, first raised the topic of Allied response in the event of Italy's entry into the war: we must strike from the air on the northwestern industrial triangle with three cities: Milan, Turin and Genoa.

In the early days, apart from minor skirmishes at the border guards, there were no major hostilities. Only on June 12, 1940 did Italian air raids begin. On the same day, the first attacks by French troops on Italian positions took place; they were all repulsed.

When the crews of the British Vickers Wellington long-range bombers of No. 99 Squadron RAF were preparing for a raid on Italian territory on June 11, their commander - Colonel R. M. Fidel - was informed by the French and military authorities that any attacks on Italy by British bombers took off from France. There were fears of retaliatory raids by Italian bombers. This led to the intervention of Churchill himself, who contacted French Prime Minister Paul Reynaud about this. Despite his interference with the local command, when the bombers began taxiing back to the runway, General Joseph Vuillemin ordered the trucks to be parked on the runway, preventing them from taking off. Moreover, civilians themselves blocked the launch of bombers at other airports.

Artillery convoy in the Alps. Pavesi M.30A tractors with Ansaldo-Schneider 105/28 guns.

On the night of June 11-12, 1940, the British Wellington and Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley long-range bombers from the 4th Bomber Command Group were tasked with attacking the Fiat factories in Turin (the Ansaldo weapons factory in Genoa was designated as a reserve target). ). Thirty-six aircraft took off from Jersey, but only 36 Whitleys reached their target. In addition, these bombers attacked two different targets. Half of them dropped bombs on Turin and half on Genoa - and only a few bombs hit the target without causing much damage. In Turin, the bombs fell far from their target, detonating near the city center, killing 13 civilians and injuring thirty more, including children. The American historian Nicholas Baker, who was then in the city with a group of foreign correspondents, recalled that four bombs exploded in a square in a poor area of Turin near a fuel tank, killing 14 people. Worst of all, however, was that in the attacked cities there were no sirens warning of an air raid, and anti-aircraft artillery did not open fire.

Of course, the Italians could not leave him unanswered. On June 12, from a base in Sardinia, Savoia-Marchetti SM.79 Sparviero bombers and torpedo bombers raided French naval and air bases in northern Tunisia. Soon they were joined by cars of the 13th and 2nd squadrons from Sicily. Airfields in the south of France were attacked by BR.20 aircraft from the 1st Bomber Regiment, covered by CR.42 fighters. Toulon, Hyères, Saint-Raphael, Calvi, Bastia and Bizerte were hit successively. On June 13, CR.42 fighters from the 23rd Squadron attacked the Fayence barracks and the Hyères airfield.

The accuracy of the Italian bombardments proved to be low due to the intensity of anti-aircraft fire, which dispersed the bomber formation. One French Vought 156 fighter was shot down and several aircraft were destroyed on the ground. Italian Takeoffs - One fighter from 82 Squadron crashed and crashed on landing. The objects of strikes of the 2nd Bomber Regiment were naval bases and ships. Two days later, SM.79s escorted by G.50s raided French bases in Corsica, while 16 Breda Ba.88 Lince bombers bombed the island's main airport.

On June 14, the day the Germans occupied Paris, the Italian military communique limited itself to reporting on the actions of small troops in several sectors of the Alpine front. An enemy attempt to capture the Galicia Pass was repulsed. On the same day, at dawn, the French 4th Naval Squadron based in Toulon (Commander: Vice-Admiral Dupla) began an operation in Italian territorial waters. It consisted of 11 heavy cruisers and 155 destroyers. These ships opened fire on oil tanks and military installations on the Ligurian coast and in the port of Genoa. Not a single Italian aircraft responded; only the coastal defenses responded with fire, taking one hit on the destroyer Albatross with a 12-mm projectile, which pierced the side, hitting the boiler room and killing 14 sailors. During the campaign in the Alps, cooperation with the German ally was limited to the exchange of technical information and intelligence contacts. XNUMX June Mussolini ordered Marshal Badoglio to conduct small offensive operations as a prelude to future operations.

offensive with more force.

In an air battle on June 15, one BR.20 bomber (1st Bomber Regiment) and several CR.42 fighters were lost, while the French lost two fighters - Devoitine D.520 and Bloch MB.151. On the same day, 12 CR.42s from 23 Squadron collided with six D.520s from 15 Squadron from GC III/6. The formation of Italian fighters was attacked by surprise and did not manage to form a defensive circle in time. The result was the loss of two vehicles, which were shot down by Lieutenant Pierre Le Gloan, second in command of the French unit. Shortly thereafter, he attacked another formation of Italian fighters over Hyères and shot down another aircraft. The battle did not end there - several Italian fighters pursued him, but the French managed to escape to the base. During this chase, he managed to shoot down the commander of the 20th squadron, Captain Luigi Filippi, with a short burst of 75-mm cannons.

On June 15, 67 CR.42 fighters from the 150th, 151st, 18th and 23rd squadrons, attacking Cuer-Pierfeu and Cannet de Morem, fought with the French D.520 and MB.151. The Italians managed to shoot down three enemy fighters at the cost of five of their own. On the night of 15/16 June, eight British bombers were deployed over Turin and Genoa. Only one aircraft overflew the target and dropped its bombs, killing 14 people.

On June 11, Foreign Minister Ciano (privately Mussolini's son-in-law), with the rank of air major, took command of the BR.20 bomber squadron stationed at the airfield in Pisa. From this airfield, he participated in raids on Toulon. After the attack on Genoa, he and his bombers flew towards Nice to find and possibly sink the ships attacking the Italian city, but due to difficult weather conditions, after a two-hour flight, Ciano and other crews returned to base without finding the enemy. The next night, out of nine British bombers, five hit the target. In total, 9 tons of bombs were dropped on Italy during this campaign, but the damage was minimal. In his Diary, Ciano noted that on 20 June he took part in the bombardments of Borga and Bastia in northern Corsica: "I hit well, but the French response was also strong and effective." Raids on the cities of northern Italy forced the Italian Air Force to create night fighter units - the first such squadron was created at Ciampino Airport in Rome.

On 16 June, a French notification from La Curieuse forced the Italian submarine Provanaa (CO: Lieutenant Commander Botta) to surface, whereupon she rammed and sank. It was the first Italian unit of this class to be sunk in this war. At the same time, SM.79 bombers from the 36th regiment dropped 9 50-kg bombs on the Menzel-Termine airfield. Five SM 79s from 253 Squadron attempted to attack the French ships south of Genoa.

On the afternoon of June 16, aircraft from the 10th Squadron bombed the Ajaccio airfield. In response, the base airfield of the Elmes unit in Sardinia was attacked in the afternoon by French Martin 167A3 bombers, but there were no equipment losses as a result of the raid. Also that day, the naval base at Bizerte was attacked by five SM.79s.

from the 8th Bomber Regiment.

On June 17, French Marshal Philippe Pétain formally demanded a ceasefire. The Italians decided to suspend preparations for the attack - but did not stop the fighting at all. On the same day, CANT Z.506B reconnaissance seaplanes joined the SM.79 bombers and together bombed Bizerte and other military installations in Tunisia. On the afternoon of June 18, Mussolini learned that Hitler had refused to sign a joint ceasefire agreement. Therefore, he ordered the resumption, or rather, finally, the start of the offensive. The air war continued. On the same day, CR.42 fighters intercepted two CAMS 55 flying boats of the French 4S1 squadron and shot down one of them.

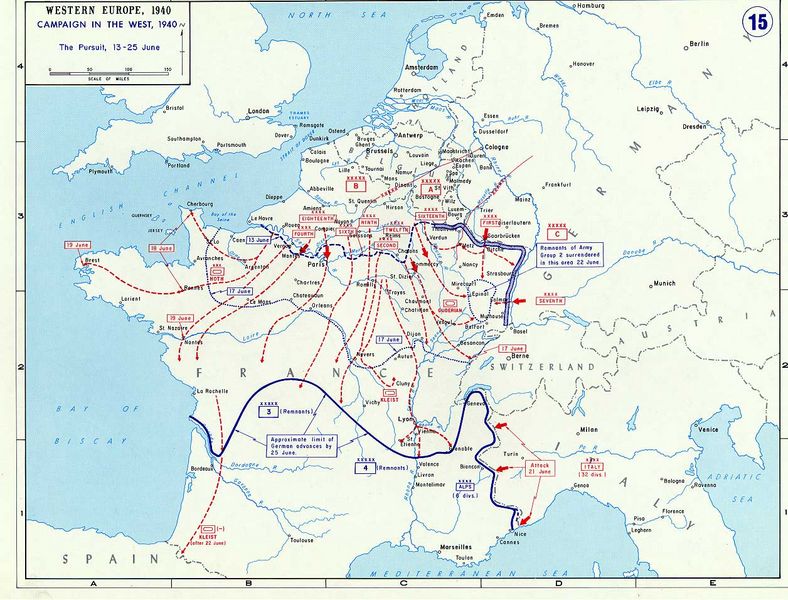

On June 20, the French government also asked Italy for a ceasefire, but the request was rejected. The attack was to take place in the coastal zone and - after crossing the mountains - to develop in the valley of the Rhone River. However, the attackers managed to capture only a few Alpine villages. On the same day, the command of the armies, corps, divisions received order No. 2329: Tomorrow, June 21, starting at 4 o'clock, the 1st and 21st armies go on the offensive. Graziani signed. However, the French were not going to be idle. XNUMX June battleship "Lorraine" opened fire on military installations in the Libyan port of Bardia, and the French Air Force attacked the naval bases in Taranto and Livorno.

Italian "offensive" on the Alpine front

On June 21 at 5:30 am, the Italian army went on the offensive, attacking the positions of the French army of the Alps, commanded by General René Olry. The Maddalena Pass, the fortifications at La Turre, and the fort at Briançon became the targets of heavy Italian artillery fire - however, the old Italian rockets, still remembering the First World War, did no more damage to the forts. The French artillery also did not remain in debt and began shelling the Italian fortifications at Chambertin with 280-mm howitzers, stopping the attack that began from this position. Only 19 of the 32 Italian divisions concentrated in the Alps attacked the French positions at dawn. By this time most of the local defense forces from the south of France had long been deployed to fight the Germans, whose troops increasingly threatened the rear of the Alpine army as they marched from the northwest along the Rhone valley.

General Orly divided his forces into two parts, one of which was sent to repel the attack of the Wehrmacht. As a result, only half of the troops placed at his disposal could defend the southeastern border from Italy. In the short campaign that followed, both sides fought with great determination. Aircraft were called in to break the French defenses, but the Italian bombers were unable to hit the small, precision-engineered, fortified targets.

Artillerymen during the shelling of French positions from 75/27 arr. eleven.

The Italian 4th Army was tasked with breaking through and capturing Albertville and thus linking up with the German attacking force from the north. According to the Italian command, this strike, together with the strike of the 1st Army in the coastal zone, was supposed to paralyze and destroy the entire French defense in the south of the country.

The Alpine corps of General Negri was the first to attack the Saint Bernard and Senj passes, having allocated for this purpose the Levanna Alpine group, the Torino division (General Paolo Micheletti), the Tridentia division (General Hugo Santovito) with half the forces of the Pusteria division ( General Amadeo de Sia). The reaction of the French gunners was immediate and very accurate - no wonder, because they knew the area very well and had been preparing for this scenario for years. Italian artillery, even mountain guns, could only fire up to the ground floor (a low ledge of rock), away from most of the French fortifications and fortifications, which could not be neutralized without outside help. In addition, the terrible weather made it impossible to use aircraft to support the attack. The rapid advance of the Italians was complicated by the lack of roads. Often there was even nowhere to organize artillery and mortar firing positions. All this caused a huge transport and organizational confusion.

Battalion Bersalle in the area of Mount Seni.

Alpine Corps in action

The main assault over the St. Bernard Pass to Albertville was to be carried out by the Alpine Corps; Belt Friction Quest on Mount Ceni - Mount Saint-Maurice was assigned to the 5th Corps. The Alpine Corps, consisting of two Alpine divisions, 4 additional Alpine battalions, a battalion of "black shirts", reinforced by 3000 artillery squadrons and corps artillery (from the 350th Corps, located on the left flank), took up positions on the Seine Pass. Opposite him were the French forts and fortifications of Solages, the forts of Traversette right on the border and the fortified region of Mount Saint-Maurice, covering the valley of the Ysere. The French garrison consisted of 150 soldiers armed with 18 machine guns and 60 artillery pieces. In addition, the defenders could count on the support of XNUMX additional battalions with another XNUMX guns.

The Italian command sent 12 battalions of their battalions to attack four French battalions defending the passes of Bourg Saint Maurice, Mont Cenis, Saint Bernard and Senj. Interestingly, the direction of their attack followed the same route as Hannibal's route to conquer Rome over two thousand years ago. Unfortunately for the attackers and for the rescue of the attacked, a heavy blizzard forced all the planes to land on the ground, and the Italian infantry recorded 2000 cases of frostbite.

In the first hours of the attack, it became clear that there would be no easy victory. The soldiers fought single battles for separate forts, fortifications and land passes. The offensive turned into a series of duels between units ranging in size from a company to a battalion - and, in addition, very bloody. Mussolini's suggestion that the resistance of the French army, already practically defeated by the Wehrmacht, would be symbolic, quickly turned out to be just wishful thinking. The forts and fortified positions of the French, surrounded by a great effort of Italian soldiers and with heavy losses, instead of surrendering, put up fierce resistance. This continued until the end of the war with France.

The Italian Alpine Corps attacked in a strip 21–25 km wide; first it was necessary to take Chapier, Setz, Tignes and destroy the fortified area around Mount Saint-Maurice. Once this was achieved, he would continue his attack on Beaufort and then on Albertville. One of the main assumptions of the offensive in this direction was the breakthrough of 8 Alpine battalions on the right flank through the Senya pass. Under the cover of fog and supported by artillery, a battalion of Bersaglieri of the Trieste division set off to storm the French positions, trying to cross the Isère river - despite the fact that the only major bridge on it was destroyed.

Despite very difficult conditions, the Italians managed to surround the fortified positions of the enemy at the St. Bernard Pass, although they did not succeed in capturing them. They stormed the Modan to break through the passes at Belcombe, Clapier, Mont Cenis and Sollerie. However, they were repulsed. On the first day, two Italian battalions surrounded the French reconnaissance units, which, under their pressure, retreated to the La Thuile barrier and further to Le Planet. On the first day of fighting, the offensive of the Italian troops was stopped on almost the entire front, with the exception of the forward sector in the Le Queira area. There, Italian soldiers surrounded the fortified village of Abries. Everything went slowly, but step by step forward. Many officers and soldiers showed courage and ingenuity bordering on insane courage; the commander of the 29th company Alpini was arrested for 10 days for recklessness and excessive exposure of the soldiers.

The right column of the Alpine units passed through the Sen' pass, but was stopped by heavy artillery fire from the Solage fortified area. After a few kilometers, the Alpine gunners flew around the enemy positions, and one part of the attacking column continued its attack on Roseland, while the other began to eliminate the positions and units of the enemy in the Solage area. The impact didn't end there. The center column fought its way through the St. Bernard Pass but soon came under heavy gunfire from Fort Traversett near the border. To reinforce the Alpini attack, reinforcements were sent from the Trieste division.

At 11:00 on June XNUMX, a battalion of motorcyclists, under the cover of fire from their artillery, broke through the pass and quickly moved towards the valley of the Jizera River. Two kilometers from the border, he reached a destroyed bridge; so he had to cross the river under fire from several French machine-gun positions. At the same time, the sappers following him, despite heavy losses, began to restore the bridge. The next day, the situation for the Italians improved only marginally. The backbone of the Italian units occupied the eastern approaches to Menton, but on the whole the offensive was not very successful.

On the morning of June 22, the CV.3 / 35 battalion from the Trieste division went on the attack, passing the motorcyclist battalion. However, he soon lost one tankette in a minefield and was forced to stop and wait for the sappers. Together with him, CV.3 / 35, "borrowed" for this action from the Littorio division, were retained. The battalion of the 65th regiment of the Trieste division began to approach Fort Traverset, but was suddenly attacked from the flank by French infantry, which was covered by the fort's crew with strong cannons and machine guns. Thus, the Italian attack failed. Another battalion of the 65th Regiment, reinforced by a company of heavy machine guns, replaced the battalion of motorcyclists and began marching to Sets.

At the same time, the left column of the Alpine Corps, having broken the weak resistance of the French on the border, moved along the valley of the Isère; its units also began to march to Settsu across the right bank of the river. By 1:30 on June 25, the Alpine Corps with its accompanying additional units managed to capture Setz, and Fort Traversett was fairly quickly surrounded - however, the garrison of the city, reinforced by the retreating units, continued to offer stubborn resistance, and its artillery continued to fire on the St. Bernard Pass. It should be noted that despite these few successes, the main attack on the St. Bernard Pass was halted by a heavy snowstorm. The assault of the CV.3 / 35 from the regiment of the Littorio division, which passed the Piccolo San Bernardo pass, also stalled. The French, taking advantage of difficult weather conditions and the weak firepower of Italian tankettes, easily stopped the attack.

In the combat zone of the XNUMXth Corps

Meanwhile, General Carlo Vecchiarelli's 25th Corps also launched an attack. Somewhat more successful were his troops advancing in the sector from Mount Chimis to Etache Pass, in a XNUMX-kilometer alley. Parts of the corps - mainly the mountain division "Superga" of General Count Curio Barabsetti di Prun, the mountain division "Cagliari" of General Antonio Squero and the division of Legnano of General Edoardo Scala - broke through the defensive lines of the border fortifications and the lines of Bessans, Lanslehans, Lanslehans, Bramans, modal and more

north of Albertville.

The 59th Corps was now to attack the 11th Mountain Infantry Division "Cagliari" (General Antonio Scuro), reinforced by the Chemsky Alpini unit, and the 1st Brennero Infantry Division with Colonel Kobianchi's Alpine unit, two Alpini battalions and other units of support. To the left of the 1st Corps was the 2nd Infantry Division "Superga", also temporarily attached to the corps. The main forces of the division moved in three columns to Brahmans and to Modan through the valley of the Ark River. The main column of the division, together with the 64th and 3rd battalions of the 63rd regiment and the 59th battalion of the 2nd regiment of the 1st Mountain Infantry Division "Cagliari", advanced through the Glazett Pass and further through the valley of the Ambin River. The XNUMXth Battalion advanced from the right across the pass of Mount Semis towards Le Planet, where it was to link up with the forces of the main column. The XNUMXth Battalion of the same regiment was advancing towards Belcombe Pass and the valley. His task was to occupy the La Villette area and link up with the main forces of the corps.

On the right flank of these forces, the Alpini "Boccaliatte" group attacked with orders to capture Bessance. To his left, in cooperation with the 59th mountain infantry division, the Chemsky Alpine formation was advancing on the Mache pass. This unit operated against the flanks of the Modan fortifications. One shot of Alpini in the lake area on Mount Seni was shared.

in the 11th Infantry Division.

The attacking force was opposed by several French forts manned by 4500 French soldiers, reinforced by two divisions with 60 tanks and artillery. After midnight on June 21, the main Italian column (three battalions) moved from the Jazette Pass towards the valley of the Ambin River; however, heavy French fire forced the attacking Italians to change direction - they had to turn to the right to take up the position of the defenders from the flank. To increase the attacking strength, the main column was reinforced by the 2nd Battalion, 63rd Regiment, 59th Mountain Infantry Division, which easily overcame the weak French resistance at the Mount Ceni Pass. After joining the main forces, an attack was launched on Brahmans.

Italian light tanks L6 / 40 enter the captured French city.

Separate columns of the 59th Mountain Division arrived at Brahmans at the end of June 22. Before the attack, the columns were divided into small assault groups in order to avoid losses from artillery fire and to be able to fight more easily in mountainous terrain. One battalion moved towards Terminion to meet Alpini's Chemsky detachment, which was attacking over Mount Bramanet. The Alpine gunners met little resistance there until they reached Fort Balm.

On June 23, the 59th Mountain Infantry Division captured the weakly defended area of the Balm fortifications without any problems and, connecting with the Alpini with Chemshchiya, launched an offensive on Modan. On the third day of fighting, the forces of the Cagliari division broke through and captured the Belcombe, Glazette and Monte Ceni passes. Alpini's Levanna group made its way through the Chapeau and Etache passes and thus finally merged with units of the Cagliari division. The Alpini Group and the Mountain Division were then able to advance towards Modane. At the same time, the troops of the Brennero division of General Arnoldo Forgiero made their way through the Monte Ceni pass. However, not everything went according to plan.

The Italian units encountered fierce resistance in the strong fortifications in the area of Villarodin and Esseion, which formed the first line of defense of Modan from the east. However, the Italians changed direction of attack and attacked from the south. The artillery was tasked with sustaining fire and silencing the defenders of the fortifications. When the war with France ended, units of the 59th Mountain Infantry Division managed to capture Villarodin and settled 2-3 km from Modan. The situation was different in the area of Mount Cenis-Lanslebourg, where the defenders offered stubborn resistance to the 3rd Battalion of the 63rd Regiment. The road along which this unit was traveling was mined, protected by anti-personnel and anti-tank fortifications, and the side approaches were heavily protected and fortified.

The Alpini unit of Colonel Kobianchi and a battalion of the 231st Infantry Regiment and a CV.3 / 35 tank battalion of the 11th Infantry Division were sent to the same area. The tankette attack was inconclusive; They were again stopped by a minefield and anti-tank gun fire. The wreckage only blocked the path of the entire CV.3/35 battalion, while the Alpini and the infantry moved forward with great difficulty and heavy losses. The well-placed and camouflaged French machine-gun positions forced the small Italian strike groups to outflank them before they were flanked. By the day of the ceasefire, these forces had managed to overcome only the first line of defense of the French.

Lucky were the Alpine shooters who managed to capture Lansleburg. Having crossed the border in difficult weather conditions (blizzards) in the area of the Chapeau and Novales passes, Alpini went into the valley of the Ribon River and - surprisingly - did not meet any French forces. Moving further along the valley of the Ark River, they reached the fortifications of Lansleburg and supported the units on the way to the fort. Boccaliate's column attacked Terminingnon, where it joined up with a battalion of the 59th Mountain Division sent from Brahmans. Unfortunately, none of the important operational goals of the corps was achieved.

The 4th Army advanced 21 km on June 22-14, but the line of French fortifications was not completely broken through. Some forts and fortified areas still resisted. An interesting document from this period survives in the collection of Walter Hule, a German military communiqué announcing Italy's unfavorable future move, with Hitler's own corrections. In the original version we read: German and Italian soldiers will henceforth march shoulder to shoulder and will not rest until Britain and France are defeated. Irritated, Hitler crossed out the words "Great Britain", then changed the rest of this passage to: ... and they will not stop fighting until they make the rulers of Great Britain and France respect the right of our two nations to exist.

On the Mediterranean

While the troops of General Guzzoni were struggling to overcome the mountain passes in the high mountains, the soldiers under the command of General Pintor launched an attack on June 22 in the Alpes-Maritimes belt. Initially, they managed to encircle the forward French posts, but they did not capitulate and continued to fight in the encirclement. In the end, the Italian attack failed under heavy artillery fire in the fortified area of St. Agnes.

General Bettisni assigned three and a half divisions to carry out the main attack: General Francesco Sartoris' Acquia, General Gulio Perugia's Forlì, General Alberto Ferraro's Cuneense, and half of General de Chia's Pusturia division. The corps of General Aricio launched an attack with three divisions: Ravenna under General Edoard Nebbi, Livorno under General Benventuo Jodi and Pistol under General Mario Pryor. General Gambara attacked with the forces of divisions subordinate to him: "Cosseria" of General Alberto Vassari and "Modena" of General Alexandro Gloria.

On the upper section of the front from the Swiss border to the south, the Italian attack crashed into the powerful defenses of the French fortified areas. At the Fréjus Pass, the Italian forces managed to break through to the Pas du Roc and Arrondaz, but their commanders set fire to each other, forcing the attackers to retreat quickly. Sergeant Luigi Boneci of the Forlì division recalls these battles thus: I fought with the French as a soldier on the Western Alpine front in the Chiappera region. We fought duels that hurt our health, because the enemy fired 305-mm shells, and our artillery had only 149/39 caliber. The same soldier also described the conditions in which the Italian soldiers fought: We had a uniform unsuitable for mountain conditions, because we were sent in summer clothes. The boots had cardboard soles and the coats were waterproof. As a result, many

soldiers got frostbite.

Occupied part of France. An officer in a black shirt visits a naval company with two French naval officers.

The main target of the attack was the fort of Cap Martin near Menton. In the first phase of the fighting, the artillery of the fort fought against an unusual enemy: it was a naval coastal defense armored train, which became dangerous because it was armed with 152-mm long-range guns. However, with the support of other guns from neighboring fortified areas, the French artillerymen managed to seriously damage echelon No. 2. Similarly armed echelons No. 5 and No. 1 with 120-mm guns fired from a greater distance. However, they did not inflict too many losses among the defenders. The firing of Italian 210-mm howitzers also did not cause much damage to the French.

On June 23, Italian assault troops finally struck directly at this fort. The soldiers attacked with great determination, defeating the first line of defense - and approached the fighting bunkers of the fort. Because of this dramatic situation, his commander ordered fire to be ferried from the neighboring forts of Roquebrune and St. Agnes. The fire of the 135-mm guns from the latter proved to be especially effective. The attackers suffered heavy losses and were forced to retreat to Mentone. However, it is fair to say that the Italians did what the Germans in the north did not: they broke into the artillery area of the fort and almost captured it.

The next day the weather turned bad; The temperature was sub-zero and it started to snow. It was similar with the attack on the Cote d'Azur, where the Italians were stopped by one bunker, in which a non-commissioned officer and seven soldiers defended. Lieutenant Giuseppe Festi of the mortar company of the 34th Infantry Regiment of the Livorno Division recalls the battles with the French: It happened during the battle for Valtinea. I ended up [as a company commander] in a small fort occupied by the French - ten soldiers and an officer who had just surrendered. The French lieutenant lost his sight from a fragment of our 81-mm mortar shell. This blinded officer wanted to congratulate me on being in command of troops that fire mortars so accurately. Since he couldn't see me, he wanted to touch my arm. A few days later, a truce was declared and the French were released. In the rear of the front, until the ceasefire on June 24, the forward outpost of Pont-Saint-Louis fought, holding the ditch under fire. Before the end of the fighting, the villages of Lansleburg and Terminion in the valley of the Arc were still captured.

Fighter aircraft were also used to attack forts and French fortifications. The pilots of the 22nd squadron on their G.50 aircraft took part in raids on one of the Alpine forts of Saute-Savoie. On June 23, SM.79 bombers from the 13th, 63rd and 252nd squadrons attacked French fortifications on the Alpine front - incl. Mont-Urs and Fort Roquebrune - to pave the way for ground forces. Air defense shot down three aircraft from the 252 squadron.

On the Mediterranean Sea, on the French Riviera, Italian troops managed to capture the city of Menton, 10 km east of Monaco; it was the furthest point scored by the Italians. Italian troops fighting in the Côte d'Azur achieved little success, approaching only a few kilometers from Nice. The Italians sent three divisions, supported by 472 guns (including many large-caliber guns), to further attack the city, but the French units stopped the attack, despite the great determination of the attackers. On the night of June 24 at 21:00, an order was received to formally sign the ceasefire.

end

On June 24, 1940, at the Villa Goliath in Rome, Marshal Badoglio accepted the surrender of French troops from the hands of the French General Hünzinger. General Olry summarized the short Italian advance in the Alps as follows: out of 32 divisions of the Italian army, 19 were in whole or in part against our forward positions, and in some cases against the main body of our six divisions. The enemy outnumbered us seven to one at Tarentaise, four to one at Maurienne, three to one at Brianconne, twelve to one at Queira, nine to one at Ubay, six to one at Tignes, seven to one at L'Ostion and Sospel, and four to one in Menton. Our leaders managed to find a rival only in Tarentaise and near Menton. All our fortifications withstood even in the environment.

Historian Raymond Klibansky wrote that ... the Duce's attack on almost defeated France not only did not bring any honors to the Italian army, but also betrayed its deplorable state. Meanwhile, Mussolini dreamed of conquering the south-east of France up to the Rhone Valley, the coast of French Somalia, Corsica, Tunisia and naval bases in Algiers and Morocco. The German Foreign Ministry compared Mussolini with a condescending smile to a circus clown cleaning the arena after a performance of acrobats and demanding a standing ovation from the public. Italians also began to call a brigade of those who wish, but only for harvesting.

During the war with France, the Italian Air Force lost 10 aircraft and 24 pilots and crew members (1337 sorties were made at the same time, including 715 bombing sorties, during which 276 tons of bombs were dropped). Enemy losses were similar - they also amounted to 10 aircraft shot down and 52 destroyed at airfields. Italian losses were 631 killed, 2361 wounded and 616 missing. There were also 2125 cases of frostbite. French losses were 37 (40?) soldiers killed, 84 wounded and 150 missing.